In psychology, “learning” is defined as a relatively permanent change in, or acquisition of, knowledge or behavior. The key term here is “relatively”, because although we tend to hold on to what we learn, it can be changed a later date.

For example, your friend teaches you how to play tennis, but later you get a qualified instructor who modifies and improves your technique.

What we learn can also be forgotten over time, especially if we do not regularly use the skills or knowledge that we have acquired.

For example, you may learn to drive a car, but if you don’t drive for several years, you will probably forget what you had previously learned and so would need to practice again.

In addition to this, in order for us to learn something, we first need to experience it at the level of sensation via our five senses (i.e. touch, taste, hearing, sight and smell). As without our senses, learning would be virtually impossible.

Below we look at some of the main theories of learning that are taught in psychology:

Classical Conditioning Theory

Classical conditioning is a term used to describe learning that has been acquired through experience. One of the best known examples of classical conditioning can be found with the Russian psychologist Ivan Pavlov and his experiments on dogs.

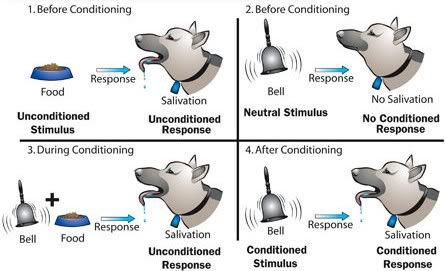

In these experiments, Pavlov trained his dogs to salivate when they heard a bell ring. In order to do this, he first showed them food which naturally caused them to salivate.

Later, Pavlov would ring a bell every time he brought the food out, until eventually, he could get the dogs to salivate just by ringing the bell and without giving them any food.

In this simple but ingenious experiment, Pavlov showed how a reflex (i.e. salivation, a natural bodily response) could become conditioned (modified) to an external stimulus (the bell) thereby creating a conditioned reflex/response.

Components of Classical Conditioning

We can gain a better understanding of classical conditioning by looking at the various components involved in Pavlov’s experiment. These are:

- The unconditioned stimulus

- The conditioned stimulus

- The unconditioned reflex

- The conditioned reflex

Let’s look at each of these classical conditioning components in more detail now.

Note: In its strictest definition, classical conditioning is described as a previously neutral stimulus which causes a reflex, where “stimulus” means something which causes a physical response.

The Unconditioned Stimulus (food)

An unconditioned stimulus is anything which can evoke a response without prior learning or conditioning. For example, when a dog eats some food it causes the dog’s mouth to salivate.

Therefore, the food is an unconditioned stimulus because it causes a reflex response (salivation) automatically and without the dog having to learn how to salivate.

Unconditioned Stimulus – This causes an automatic reflex response.

Conditioned Stimulus (bell)

The conditioned stimulus is created by learning, and therefore, does not create a response without prior conditioning.

For example, when Pavlov rang a bell and caused the dogs to salivate, this was a conditioned stimulus because the dogs had learned to associate the bell with food. If they had not learned to associate the bell with food, they would not have salivated when the bell was rung.

Conditioned Stimulus – You need to learn first before the stimulus will create a response. It is an acquired power to change something.

Unconditioned Reflex (salivation)

An unconditioned reflex is anything that happens automatically without you having to think about it, such as your mouth salivating at the smell of food.

Unconditioned Reflex – A reflex that happens automatically and you didn’t have to learn how to do it.

Conditioned Reflex (salivation in response to bell)

A conditioned reflex is a reflex that you have learned to associate with something. For example, the dogs salivated when Pavlov rang a bell, when previously (without conditioning) the bell would not cause the dogs to salivate.

Conditioned Reflex – A reflex that can be evoked in response to a conditioned stimulus (i.e. a previously neutral stimulus).

Behavioral Patterns of Classical Conditioning

The word conditioning is used to mean a type of learning that occurs without you having to think about it, almost like an automatic type of learning. Although later on, this learning may be reinforced by reflecting upon that experience.

For example, sometimes you will see a dog flinch when you raise your hand. This flinching is a conditioned reflex, and can be seen in dogs who have been mistreated by their owner.

The same can be found in women who are beaten by their husbands. This latter example shows that classical conditioning is not solely confined to animals, as it can just as easily occur in humans.

The three main behavioral patterns that are associated with classical conditioning are:

Extinction

Extinction occurs when the conditioned stimulus is presented a number of times without the unconditioned stimulus.

For example, if we ring a bell and cause a dog to salivate, then we have a conditioned stimulus. But if we keep ringing that bell without giving the dog any food (unconditioned stimulus), then eventually the dog will disassociate (unlearn) the bell from the food and so will no longer salivate. Therefore, extinction has occurred because the bell no longer has any effect on the dog.

This process of extinction is used by psychologists to help people overcome their fears or phobias.

For example, if you have a strong fear of heights, then by constantly exposing yourself to heights you will eventually unlearn your fear via a process known as desensitization.

This can be done through immediate exposure, whereby you go to the top of a very tall building immediately. Or by gradual exposure, where you gradually work your way up a tall building floor by floor.

Note: Extinction is different from forgetting, because extinction involves unlearning something.

In brief: Extinction occurs when we unlearn something, or become desensitized to it, and the stimulus no longer creates the effect it used to cause.

Stimulus Generalization

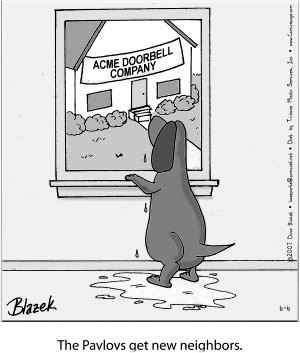

Stimulus generalization occurs when a stimulus that is similar to a conditioned stimulus creates the conditioned reflex.

For example, if we can make a dog salivate by ringing a bell (conditioned stimulus), and we can make the same dog salivate by ringing a slightly different sounding bell, then what we have demonstrated is stimulus generalization.

In brief: Stimulus generalization occurs when something similar to our conditioned stimulus creates the same response (the conditioned reflex).

Discrimination

Continuing from the example above, if we were then to use another bell which produced a different sound but this time the dog did not salivate, then what we have demonstrated is discrimination because the dog no longer associates that sound with food (i.e. it has discriminated against it).

In brief: Discrimination occurs when our new stimulus is too different from our original conditioned stimulus to cause the effect we want (the conditioned reflex).

Operant Conditioning Theory

Operant conditioning is a term used to describe behavior which has been reinforced by reward or discouraged through punishment. For example, if a mother wants her daughter to clean her room, then she may give her some candy every time she cleans it.

Given enough time, the girl will start to clean her room more often because she knows that she will get some candy in return for doing so.

As a result, the girl’s behavior (cleaning her room) has been modified (conditioned) because she has learned to associate a behavior with a reward.

Although this may sound similar in principle to classical conditioning, it is in fact different because operant conditioning requires action on the part of the learner.

As a result, the girl will not get any candy until after she has cleaned her room. In classical conditioning, the conditioned stimulus (candy) is used regardless of what the learner does.

The following video discusses the difference between classical and operant conditioning in more detail.

Note: Operant behavior is defined as actions which have consequences.

The Skinner Box

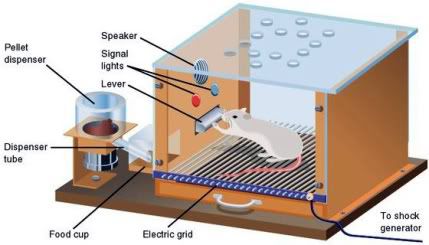

It was B.F. Skinner who is best known for operant conditioning and the device he invented to research it, a device called the operant conditioning apparatus or the Skinner Box.

The Skinner box involved placing an animal (such as a rat or pigeon) into a sealed box with a lever that would release food when pressed. If food was released every time the rat pressed the lever, it would press it more and more because it learned that doing so gives it food.

Lever pressing is described as an operant behavior, because it is an action that results in a consequence. In other words, it operates on the environment and changes it in some way.

The food that is released as a result of pressing the lever is known as a reinforcer, because it causes the operant behavior (lever pressing) to increase. Food could also be described as a conditioned stimulus because it causes an effect to occur.

It is important to note though, that there is a difference between a reward and a reinforcer in operant conditioning.

A reward is something that has value to the person giving the reward, but may not necessarily be of value to the person receiving the reward.

A reinforcer is something that benefits the person receiving it, and so results in an increase of a certain type of behavior.

Below are several of the different ways to categorize a reinforcer.

A positive reinforcer has some sort of value to whoever is receiving it. For example, food when you are hungry or water when you are thirsty. A positive reinforcer serves to increase an operant behavior.

A negative reinforcer has no value to whoever receives it. It may also injure, harm or cause discomfort in some way. For example, a very hot room, an electric shock or a dangerous situation.

A negative reinforcer causes the recipient to try to escape from it or avoid it. For example, if a room is very hot, then you may switch on the air conditioning or a fan to try to escape from the heat.

If this is successful, you are likely to repeat this behavior the next time you are in a very hot room. Negative reinforcers therefore also serve to increase operant behaviors.

Note: Negative reinforcers are not a form of punishment because they precede (i.e. come before) an operant behavior. Punishment occurs after a behavior has already occurred, such as smacking a child after they have done something bad.

Another way to classify reinforcers, are as a primary or secondary reinforcer.

Primary reinforcer

A primary reinforcer has some value to whoever is receiving it, and this value has not been learned. For example, food when you are hungry or water when you are thirsty.

Secondary reinforcer

A secondary reinforcer has an acquired value to whoever receives it. This means that you are taught its value/worth over a period of time before you see it as being valuable to you.

For example, money is a secondary reinforcer because you have to learn the value of money and what it does before it has any meaning to you. If you are short of cash, then receiving money can also be categorized as a positive reinforcer because it has value to you.

Extinction

Just like in classical conditioning where presenting a conditioned stimulus a number of times without the unconditioned stimulus results in extinction, a similar process also occurs in operant conditioning when an operant behavior begins to declines.

For example, if a rat receives no food when it presses a lever (reinforcement is withheld), then it will gradually press that lever less and less until eventually it stops doing so entirely.

In effect, the rat gives up on pressing the lever (stops an operant behavior) because it no longer results in it receiving food (reinforcer). The operant behavior has therefore become extinct.

Stopping bad habits

This knowledge of extinction can be applied to behavior shaping, such as when trying to stop a bad habit.

So rather than trying to punish a certain behavior, it is usually far more effective to take away the reinforcer(s) associated with it.

By doing so, the habit will no longer be seen as having any benefit, and so the undesirable behavior will gradually start to fade away (extinction).

Punishment may temporarily reduce a certain behavior, although in the long run, because that behavior is still seen as bringing some sort of benefit, it will continue.

In addition to this, punishment can also make the person being punished resent you and then do things behind your back out of spite.

Partial reinforcement

Behavior that is acquired under partial reinforcement is much more resistant to extinction than behavior which has been acquired under continuous reinforcement.

For example, if a rat receives a reinforcer every time it presses the lever, then this would be continuous reinforcement. However, if the rat receives a reinforcer at random, or every second or third time it presses the lever, then this would be partial reinforcement because it does not get the reinforcer every time.

If you were to stop giving the reinforcer, the rat receiving partial reinforcement would display a greater resistance to extinction (i.e. it would keep pressing the lever for longer after the reinforcer had been stopped).

A good example of partial reinforcement can be seen in casinos. This is why you will often find that despite winning a large sum of money, many gamblers are unable to stop and end up losing all of what they had won.

Discriminative stimulus

In a slight variation of the original Skinner box, a light bulb was placed above the lever.

Whenever the light is on, pressing the lever would result in the rat receiving the reinforcer. But when the light is off, pressing the lever would result in no reinforcer.

Given enough time, the rat eventually learns to only press the lever when the light is on and ignores the lever when the light is off.

Skinner called the light a discriminative stimulus, which he defined as a stimulus which allows the animal to tell the difference between “a situation which is reinforcing and one that is not”. In other words, the light allows you to determine whether or not you will get a reward (reinforcer).

Some real life examples of discriminative stimuli include hearing a bell before lunch or seeing a traffic light when you are driving. In both cases, a signal (bell/light) tells you what sort of reinforcement you will receive in that situation.

Putting this all together, you can now see that operant conditioning is a modification (conditioning) of an action (operant behavior) which has consequences (e.g. lever pressing releases food) through the use of positive reinforcement or negative reinforcement.

Observational Learning

Observational learning occurs when a behavior is acquired by watching the behavior of someone else. This second person is known as a “model” and either intentionally or unintentionally demonstrates a behavior to you.

If the observer is able to identify with this behavior and receive some sort of satisfaction from it, then they are said to have received vicarious reinforcement (imagined gratification).

For example, if your favorite sports team wins a game, then you receive an internal sense of satisfaction as a result of their victory. You have received vicarious reinforcement, which may then motivate you to play that sport.

Vicarious reinforcement can occur in virtually any circumstance in which you, as the observer, receive some sort of gratification from watching the behavior of another person (the model).

Social Learning Theory

Social learning theory is an expansion of observational learning, and deals with how social groups can be affected by their environment.

A good example of social learning theory can be found amongst teenagers who follow various celebrity role models.

If the teen receives some sort of gratification (vicarious reinforcement) from observing the behavior of their role model, then they are likely to adopt a similar type of behavior.

For example, a teen that idolizes a rock star may start playing a musical instrument such as a guitar. As a result, their behavior has now been altered.

We can further subdivide the type of behavior we acquire as a result of social learning into either prosocial or antisocial behavior.

Prosocial behavior

Prosocial behavior is behavior that benefits another person, a group of people or society as a whole. For example, if a child learns to recycle and live an environmentally friendly lifestyle from their parents, then they are likely to act that way for the rest of their life.

Their behavior is prosocial, because it benefits the environment and society as a whole.

Antisocial behavior

Antisocial behaviour is behavior which is destructive to others and very often to yourself.

For example, a teen who steals from other people or who vandalizes property is exhibiting antisocial behavior, because it is destructive to other people and the surrounding environment.

Latent Learning

Latent learning is learning which occurs without reinforcement, and which may later be reactivated with a reinforcer. For example, if a rat is left in a maze, it will randomly explore that maze and try to find a way out.

If we repeat this several times, the rat may appear to exhibit the same type of behavior where it randomly explores the maze looking for the exit. Although the rat has been in this maze several times, it appears not to have learned anything because it still takes a long time to get out.

If however, we were to then introduce some food into the maze (a reinforcer), the rat would quickly learn to escape the maze. Almost as though it suddenly learned how to do it. The purpose of the reinforcer was to act as an incentive, which activates what the rat had previously learned.

In this case, the first few times the rat was exploring the maze it was learning, even though it appeared not to be learning anything.

When we added food to the maze, this prior learning which had remained latent (dormant), suddenly became reactivated thereby allowing the rat to use its previous knowledge of the maze to quickly learn the escape route.

Basically, what this all means is that you learn things through experience, even though you may not think that you are learning anything at the time. Later, if something reactivated what you had (latently) learned from that experience, you will then be able to learn it very quickly.

For example, when you are at school, one of the best ways to improve your understanding of a subject is to research it before you are meant to learn it.

So if you have a lecture next week, by studying for that lecture now you will be able to understand it better and faster once you actually take that lecture. Your prior latent learning has allowed for an accelerated future learning.

This is hardly surprising if you look at things from the perspective of the brain, as when you learn something, you form neural pathways in the brain related to that activity.

This means that the next time you do it, your existing neural pathways will be strengthened and refined thereby allowing you to perform better.

Latent learning may therefore be described as the creation of these pathways, which provides a foundation for future learning.

This is why it is important to expose your mind to as much information as you can about a subject, because even though it may seem difficult now, the next time you come across it, you will find things to be a lot easier.

Insight Learning

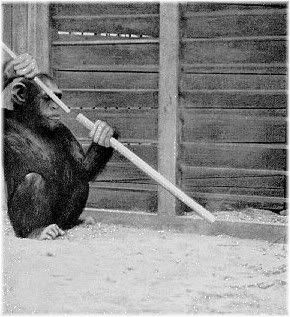

Insight learning is an “a-ha!” moment, when something suddenly seems to click into place and make sense. A good example of this can be found with research done by Wolfgang Kohler on an ape called Sultan.

Sultan was put in a cage and given two sticks which could be clicked together to make a longer tool. Slightly outside the reach of the sticks was an orange.

Sultan spent a lot of time trying to get the orange. First with his hands, and then with the sticks. However, he was unable to reach the orange no matter what he did.

Then one day Sultan clicked the two sticks together, and was able to reach the orange. This “insight” that Sultan received, came as a result of his past attempts to get the orange and a reorganization of those experiences.

So whereas previously Sultan had two seemingly useless sticks, he now had a useful long stick, something which he did not have the insight to see before.

So insight learning is an insight into our past experiences, from which, we can then use to solve problems we were previously unable to. This has most likely happened to you many times.

For example, someone may be trying to explain something to you, but no matter what they say, you just don’t seem to “get it”. Then, all of a sudden, it clicks and “a-ha” you now see what they were trying to say.

Resistance to extinction

Since insight learning is acquired as a result of past experiences, it tends to be fairly resistant to forgetting. In other words, “once you’ve got it, you’ve got it”.

On the other hand, if you were to learn something simply through memorization, then you are likely to forget what you had learned very quickly.

This is why it is extremely important to try to actively apply what you mentally do, to solidify that knowledge in the brain.

If you are at school, and are trying to learn a subject well, then a good way to solidify your learning would be to teach it to someone else as you will now be actively using your mental knowledge.

Learning to Learn

Learning to learn describes the use of learning sets in learning. Basically, it states that we become better at what we repeatedly do.

So for example, if you solve crossword puzzles, then over time you are likely to find them easier and easier and so will need harder puzzles to challenge you.

The same applies to learning a new subject. At first it seems hard, but the more you study it, the easier it becomes.

The idea of learning sets first came from research done by psychologist Harry Harlow, who tested a monkey’s ability to find a grape under a container.

The test was to see if the monkey could discriminate between the two different shapes of the containers, by getting the grape from the underneath the correct container.

What Harlow found was that after the first exercise, the monkey’s ability to discriminate between different shapes (and get the grape) in subsequent exercises rapidly increased.

The monkey was said to have acquired a learning set, using previous knowledge to quickly solve future problems.

The Role of Memory

Memory is defined as the ability to retain knowledge, and is therefore necessary for learning.

The process of memory involves three main stages:

- Encoding

- Storage

- Retrieval

Let’s look at each of these now.

Encoding

Encoding is the process of making information meaningful to you, and a good example of encoding, can be found with anagrams.

For example, if you are presented with the letters ABT they would be meaningless to you. If however, you are told that ABT represents an animal which can fly, then you can rearrange those letters to form BAT which now has meaning to you.

Storage

Storage is the ability to retain information for a period of time, and can be further subdivided into short-term memory and long-term memory.

Short term memory (STM)

Short term memory is also called working memory. It allows you to hold onto information for a few minutes, after which, you will then forget it.

Long term memory (LTM)

Long term memory is information which has been more or less permanently stored. This type of memory is what allows you to remember your past.

Long term memory tends to be associated with short-term memory, because if your short-term memory is impaired, then this will interfere with your capacity to form long-term memories.

Retrieval

Retrieval occurs when you access a previously stored memory. In other words, it comes into your conscious awareness.

There are three main processes which can occur during the retrieval of memories.

1) Recall

Recall is the ability to easily recall a memory. For example, you know what your friend’s name is.

2) Recognition

Recognition occurs when something helps you to remember something else. For example, a multiple choice test will contain one correct answer. When you see the correct answer, it will help you to recall any previously stored memory that you may have of it.

3) Repression

Repression occurs when a memory is forced into the unconscious in an attempt to protect the ego from some sort of psychological threat. For example, a painful or traumatic experience in your life.

Reviewed – 1st April 2016